Over the past few days, I’ve been drafting media releases to accompany samples of our new vintages. As I worked on the backstories, I realised just how much time I spend trying to articulate the connection between the wine in the bottle and the place where the grapes were grown. Having worked with dozens of growers across NSW — some for many years now — the unique stamp of each vineyard is undeniable. Year after year, the same sites seem to leave their signature on the wines. And yet, while we can taste it, this remains hard to contextualise, and harder still to prove.

In terms of broad chemistry, two wines from the same region, crafted in the same way, might appear almost identical in composition, yet entirely different in personality. So, if it’s not only chemistry that defines a wine, then what is it? What makes my wine appear utterly unique from that of my neighbour?

For me, such extraordinary – almost mystical – aspects of winemaking can only be explained by one thing…

In previous editions of The Love of Wine, I’ve shared various memories of my experience training as a young winemaker in France’s picturesque Alsace region, more than twenty years ago. During one such recollection, I mentioned being profoundly impressed by the way I felt Francis – the winemaker I worked under – appeared so ‘connected’ to his wines and the vineyards he managed. It seemed like every discussion — whether about wines we were making or simply enjoying — circled back to the vineyard sites, often with vigorous, passionate detail.

What struck me was not only the level of attention, but the language. Francis and his peers had a whole vocabulary for linking a wine to its place. Unlike the winemaking conversations I’d become used to in Australia, their focus was far less on who made the wine, and much more about where it came from.

This belief – that above all, wine is a unique expression of the time and place in which it is grown – is ancient and central to the philosophy underpinning the production of so many European wines, particularly the exceptional ones. And in French, this is captured in a single word with no real English equivalent: terroir.

The legendary wine critic Jancis Robinson MW deciphers terroir through layers of the environment: soil and topography, interacting with climate at every scale — macro, meso, and micro. Together, these elements give each region, site, even vine row, its unique personality, expressed in the glass year after year.

So central is terroir to European winemaking that entire quality control and regional production regulations are based upon it. For example, under France’s Appellation Origin Controlee (AOC), to produce a wine labelled ‘Grand Cru’ in Burgundy, the grapes (of a regulated variety — either Chardonnay or Pinot Noir, depending on where) must be grown in one of the designated ‘Grand Cru’ sites, made in accordance with strict winemaking guidelines and even packaged and labelled to specification. The wine is inseparable from its place of origin.

The strength of such a system is clear: it protects regional identity and creates a baseline of authenticity. When you buy a Grand Cru Burgundy or a first-growth Bordeaux, you know the origin, variety, and intent — and more often than not, you taste greatness.

But there are drawbacks. Rigid rules can stifle creativity, limiting how growers and winemakers evolve with changing times. They also impose value barriers: is anyone likely to pay more for a ‘Village’ wine than their neighbour’s ‘Grand Cru,’ even if the quality rivals it? The difference can be as arbitrary as a fence line.

Across Europe, these classifications can make or break a grower’s prospects. Yet exceptions abound: young winemakers outside the hallowed crus are producing thrilling wines precisely because they are free to experiment — with varieties, methods, and even packaging. Do they care less about terroir? I don’t think so. In my experience, terroir is in the DNA of every European winemaker, whether they follow tradition or challenge it.

What fascinates me is that the AOC system — principally about geography — actually extends into winemaking practice and even presentation. To me, this reinforces a broader truth: terroir isn’t just where grapes are grown, but also how a wine is made and even enjoyed.

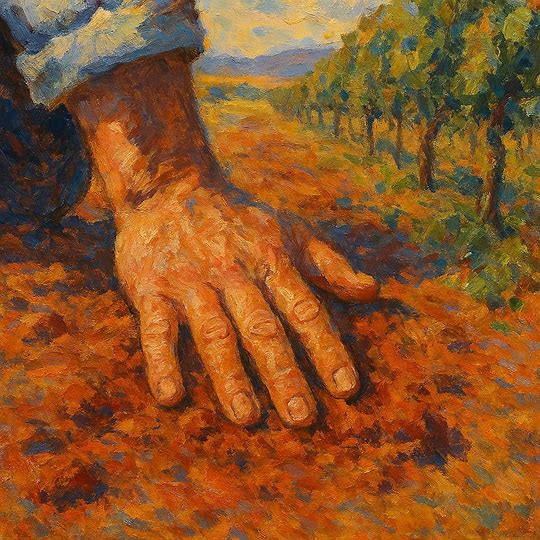

In this way it flows from geography into culture and community. For families who’ve worked the same vineyards for generations, terroir is almost instinctive — knowledge passed down through practice and ritual. Having come from outside such traditions, I can see why I was so captivated by Francis’ deep, intuitive relationship with the land and his wines.

I appreciate this sounds all well and good, and certainly leans into the romance and magic around winemaking, but is terroir a real phenomenon? Can a wine truly taste of the place it comes from? And does scientific fact support the subjective evidence? Well the answer is yes, and no.

It’s easy enough to show how the unique qualities of a vineyard like aspect and elevation influence grape chemistry and, therefore, the sensory qualities of a wine, but the impact of arguably the most important and often discussed aspect of terroir – soil – is far more debatable. Again, there are characteristics of a soil profile – like nutrient status and water availability – that are easily measured and can be linked to grape and wine chemistry, usually via their impact on fruit yield and vine health. But when growers, winemakers or other terroir-enthusiasts claim to taste in a wine various attributes of the soil in which the vine is cultivated, scientific support fades away.

And yet, when I talk about our Canberra District Riesling, I will frequently reference how the limestone bedrock lying deep below our vineyard in Gundaroo imparts a fine line of natural acidity and a delicious minerality – a slight salinity and slate-like texture – to the palate. I will similarly remark at how the sandy-loam soils of the Will’s Hill vineyard in Lovedale tend to deliver Shiraz of bold fruit drive, versus the more savoury, spice-laden wines born from the volcanic basalts found in the higher reaches of central Pokolbin. These remarks are made after seeing the same attributes present year after year. Yet, the science says soil is simply unable to influence the aroma, flavour, or structure of a wine in this way. There are no known pathways for minerals contained in the soil, let alone the bedrock, to do this.

So perhaps fully embracing the concept of terroir requires a small leap of faith.

Some years after my time in France, and now well into my winemaking career, I came across another perspective that shifted my thinking again. In Max Allen’s The Future Makers, he recounts a lecture given by legendary winemaker Geoffrey Grosset. Geoffrey spoke about the Aboriginal word Pangkarra, used by the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains to describe the unique qualities of their land — topography, climate, sunshine, soil, and more — in much the same way the French use terroir.

That discovery resonated deeply. It showed me that describing the character of a place in this holistic way wasn’t only a European invention, nor was it a conceit of wine snobbery. It is a way people across cultures have connected with the land for generations. Perhaps the lack of an English equivalent reflects how recent our arrival to so much of the world has been, and how disconnected we still are from the environments we inhabit.

To this day, I treat the concept of terroir — or Pangkarra — with reverence. I value it deeply, but I also know I will never understand it as profoundly as those whose connection to the land spans countless generations. To these people, I am just happy to listen.

Kind Regards,

Matt Burton

P.S. If this story lands with you or sparks any memories of your own unexpected wine experiences, please feel free to send me an email – I’d love to hear from you!

You can read previous editions of The Love of Wine on the News & Events page of our website, here.